Monday, 30 May 2016

24 July 1880 - 'A Girls' Walking Tour' by Dora Hope - Part Two

Wednesday morning - much refreshed, we rose with the lark (unless, indeed, that estimable bird rises before 7.30), and having had our usual substantial breakfast we went on our way without staying to inspect the lions of Farnham, or even to inquire if there were any.

"I'm sure we may congratulate ourselves on having good tempers," said the poet, as we stepped briskly along in the bright morning air, "because my father prophesied that we should all have quarrelled with each other before the first day was over, and should probably part and return to our respective homes on the second."

"But why should we quarrel any more than anyone else?" asked one.

"Well, I could not quite grasp his reason, but he said people always do on walking tours; it's a way they have, I suppose. They get so tired of each other's society after a day or two."

"Naturally, they do, when the pedestrians are of the male sex," said our artist, who is something of a man-hater, "and very likely we should have been no exception to the rule had there been any gentlemen with us, so I think we have clearly proved that our arrangement is the best." Of course we all agreed, and rather than let the prediction come true I forbore for the future to express my opinions with regard to the cooking-stove, since the others all seemed peculiarly impressed with the conviction that it was the secretary's duty to carry the obnoxious machine.

Exhilarated by the fresh air and bright sun, we walked at a fine pace towards the wild barren country round the Hind-head, intending to stay the night at Haslemere.

Tilford was soon reached, and here we paused to buy provisions and also to inspect a splendid old oak tree on the green.

"It is called the King's Oak," said the pathfinder, "and is one of the boundary marks of the Waverley Abbey lands. Years ago orders were given for it to be cut down; but the country people assembled from far and near to protect the tree, which they regarded with great respect and even affection. They nailed plates of tin round the trunk so that the axes could not take effect." Seeing what she took to be incredulous looks, she added - "There are the pieces of tin before your eyes, so it must be true."

Whether the pathfinder's pretty story were true or not, we could not but be glad that the hoary old tree had stood so long, and such as were able made some hasty sketches of it, whilst the others went on an expedition to the one shop of the village, and secured a heterogeneous collection of viands for dinner.

As we left Tilford with its pretty bridge and river behind us, the aspect of the country grew wilder, and cultivation began to give place to heather-clad hill and wide breezy moor. The road was very dusty and glaring white. The sun, mounting high in the heavens, blazed down upon us, making us pine for the sight of a tree or anything that would cast more shade than a small umbrella; but we pushed on bravely till the strange mounds called the "Devil's Jumps" were clearly visible.

At this point a very unexpected "ten minutes' interval" took place. It is superfluous to relate that we owed this halt to our president, who, spying a small lake lying placid among the heather a short distance from the road, insinuated how delightful a closer investigation of it would be. The pathfinder warned us of the distance still to be traversed, and expatiated on the beauties which would soon be unfolded to our wondering view; we looked at the hot white road, then at the clear cool water. Alas! The temptation was too strong, and, headed by the president, we set off at a run, away from the path of duty, feeling rather like Christian and Hopeful when straying into Bye-path meadow. We did not, however, like them, come to repent having strayed, for of all the delightful remembrances of our tour, none is looked back to with more pleasure than the rest beside that lonely lake.

We lay down on the springy heather, most luxurious of couches, revelling in the floods of sunshine, whilst a gentle breeze fanned our hot faces as we gazed up into the cloudless blue overhead. We drank from the transparent water, where a tiny waterfall rushed over the stones in mimic wrath. We watched the caddis-flies and other "strange creepy creature" cutting capers in the water, all unconscious of the curious eyes marking their every movement, whilst a lark, hidden from view in the clouds, trilled forth its glad song "thanking the Lord for a life so sweet." The babble of the fairy cascade, the sound of insects humming drowsily, and the bird's song just broke the stillness that otherwise would have been oppressive. All too swiftly the moments flew by, we each knew we must soon be moving onwards, and yet dreaded hearing the pathfinder give the signal. Suddenly, looking at her watch, she started to her feet and exclaimed -

"Oh, it's actually twelve o'clock! How could I let you waste so much time by this silly little pool! You must shoulder knapsacks instantly. Come, wake up, president. Now, secretary, I long to hear the cheerful jangle of the stove again."

With much regret we obeyed her behests. Leaving our lovely resting-place, we were soon marching along the fine country road, and shortly began the actual ascent of the Hind-head.

Two hours' walking brought us to a belt of firs on the road side, in the cool depths of which we lunched, getting water for tea from a well hard by, said to be 200 feet deep. No misadventures occurred, except the usual one of setting fire to the grass by the stove-lamp. As this happened almost every day, we became very expert at extinguishing conflagrations of this sort, and ceased to notice them much, though at first they proved rather exciting.

We were very expeditious over our repast, having already spent too much time on the road; indeed, we were all anxious to start again quickly, for the scenery through which we were passing became more and more grand, and we longed to be at the top of the hill to see the view which we knew was in store.

"How far is it to the Devil's Punch Bowl?" asked the pathfinder, of a rustic sitting astride a low stone wall.

"Dunno, never yeard tell on't," was the stolid answer.

"What ignorance!" murmured she, and hastened on to ask a woman approaching. This individual seemed to have the very vaguest ideas of distances, but hazarded in reply, "It moight be about three moile." The next pedestrian declared it to be a "good foive moile," whilst still another said even rather than that.

Our guide concluded not to ask any more questions, so we trudged on. The strange parallel valleys causing the road to make a wide detour, possibly accounted for the difference of opinion about the distance. At last we reached the celebrated Punch Bowl. No doubt every one who knows Surrey will be familiar with this spot - one of the finest in that beautiful county. Standing there, half way up the Hind Head, one sees range upon range of bleak rounded hills. Conspicuous among them are the three conical peaks mentioned before as marking the jumps taken by the individual said to own the Punch Bowl. Behind, the ascent is more abrupt and steeper than that of the road by which we have come. At our very feet is the great hollow scooped out in the bosom of the earth, so sudden and unexpected as readily to account for the superstition which gave its name.

On its brim is a tombstone, erected to the memory of an unknown sailor foully murdered on this spot, and whose tragic end is set forth in a curious inscription. Coiled about the base of the stone lay a viper recently killed, perhaps by some passer-by. This gave the finishing touch to the weird, unnatural character of the scene. Gazing, in a silence unbroken by voice of any living thing, it was with almost a sigh of relief that we heard the sound of sheep-bells tinkling faintly far below us. We then saw for the first time, dwarfed by distance, but still recognisable, a substantial and most unghostly farmhouse nestling amongst the trees in the very Punch Bowl itself.

With that, all our eerie feelings vanished, and then someone remembered that this place is mentioned by Nicholas Nickleby, he having stopped to rest here when on his way to Portsmouth with poor Smike.

Turning away from the melancholy scene, we were soon at the top of the hill, whence a wonderfully extensive view is obtained. From thence a picturesque lane, whose high hedges sent forth long trails of honeysuckle, clematis, and rose, led to Haslemere, our goal. We had, for some reason or other, all been filled with intense admiration for Haslemere, never having seen it. Perhaps we rather associated it with the poems of the Laureate who lives there. However, our expectations were high, and, as is nearly always the case when one expects much, we were disappointed.

The pathfinder and myself had gone to reconnoitre, and we read in each other's faces the tale of blighted hopes.

"Oh, pathfinder, we cannot stay here, it's so very tame after what we have come through," I exclaimed.

"It is; painfully so," said my companion; "and see, the sun is not thinking of setting yet, it won't be dark for hours. Do let us go on again."

"But where to? And what will the others say?"

"Oh, if we settle all before they arrive and then just say we are going on to such and such a place, they will take it quite calmly."

Consulting the map, we found the next village to be Fernhurst, which sounded charming to us, and some women standing near told us there was sure to be accommodation there, as there were two inns, which could not both be full. Thus encouraged, we went to meet the others, who, hearing it was only two miles to Fernhurst, were quite satisfied with the arrangements.

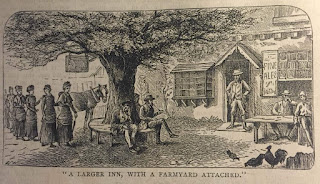

It was rather a dismaying discovery to find the "two inns" to be really nothing more than small public-houses, and quite impracticable, but hearing of a larger inn with a farm attached a mile away, we started on again, hopefully. The pathfinder and I feeling responsible in this matter, as we had been the ones to decide on leaving Haslemere, went quickly on, feeling a trifle anxious lest there should not be room at the "Old Ewe's Head." It proved to be indeed the beau ideal of an old-fashioned country inn, standing back from the road, with a little green in front, in the middle of the which was an immense patriarchal elm tree, whose branches, stretching out all round, nearly touched the trees on the other side of the road. Round the great gnarled trunk were seats ranged, on which doubtless, the lords of the creation resident in the neighbourhood would sit, when the day's work was done, smoking their evening pipe, and talking over the affairs of the nation.

The landlady, a buxom and highly good-natured dame, was really distressed to find re required more than one small room, which was all she could offer. This being the melancholy fact, my companion and I were, for the moment, plunged into a state of abject despair. The only information the landlord could give was that we were nine miles from anywhere. "Ah, yes," he said, "it's a good nine mile afore you'll come anywhere worth mentioning; and a lonely road, too, a very lonely road, it is. Well do I remember when I was a lad going down that road of a morning with the other lads to see the gibbet, and sometimes there'd be as many as three bodies hanging there all at once; just opposite that pond as you'll see, 'bout two mile from here, where the trees meets over your 'ead now, that's where them gibbets used for to stand. Yes, a very lonesome road it is, and no mistake." He continued in this strain for some time; we had gone out to consult him whilst the tea we had thought it prudent to have ready against the others' arrival, was being prepared. Happily, the landlady broke in upon his enlivening information by coming to say the kettle was "just on the boil" and that tea would be ready in a minute.

"What's my old man been telling you about nine miles from nowhere, ladies? I heard him through the window; but never you heed him; he was always such a one to put the worst side upmost. I'll set you on the road as'll bring you to Midhurst under five miles, so you'll get there 'fore it's dark if you go as quick as you was when you come here. And as for them gibbets, he knows as well as I do that they've been all took down and done away with these forty years; so don't you heed him, ladies."

This was reviving, and we felt ready to fall upon her neck and weep for joy, but refrained, and greeted our companions with a sprightly air, refusing to tell them anything till after tea. And what a tea that was! Such new-laid eggs and fresh butter, such cream and new bread, and the giant water-cress, home-made jam, and native honey, combined with all the other good things, made up a repast not soon to be forgotten. And how the eatables vanished! We might not have eaten for a week, to see how quickly the table was cleared. At last we were satisfied, and with many directions from the kind hostess and predictions of evil from her saturnine spouse, we set off on the last stage of that long day's journey.

A lovely walk it was. Through the roadside trees were seen distant hills bathed in the ruddy sunset glow, and the sky, where visible through the green roof overhead, was flecked with amber and crimson and gold. The sunset was a glorious one, but it reminded us that darkness would soon follow, and we must hurry on. And hurry we certainly did , too much so, perhaps, as it soon became evident that we had missed the way among the many short cuts recommended.

After floundering wildly about for a little, we were soon hopelessly lost, so we stopped, to hold a council of war. The pathfinder and I volunteered to scour the country round till we met with either a house or a person to ask. Climbing to the top of a five-barred gate, from whence a very extensive view is obtained, I surveyed the prospect o'er till I discovered - oh joyful spectacle! - a house. The guide and I hastened to it, and our thanks will be for ever due to the lady of that house, who, with the greatest kindness, put us in the right road, by which a mistake would be impossible.

"Putting our best foot foremost," we went along at a good pace, singing "Marching thro' Georgia," and other martial airs, when sure there was no one "around," till at last our long walk was over, and we were peacefully ensconced in our hotel at Midhurst, having come twenty-three miles.

Next morning our rule of early rising was, for the first time, broken, in fact I fear it was nearly nine o'clock before we gathered round the breakfast-table. We all felt rather stiff, and some of us even a little foot-sore, though our constant practice of bathing the feet in warm water, with a few drops of arnica therein, saved us from much suffering in that way.

After visiting the beautiful ruins of Cowdry, we crossed the park and gained the high road to Petworth. We were rather curious to see this little town, having heard a story of a regiment of soldiers which was ordered there. They marched what seemed to them to be more than the proper distance without apparently getting an nearer to the town; they then made inquiries and learned that they had already passed through the place, without being aware of the fact, and were marching back to London! I think the town must have considerably changed since this extraordinary thing took place.

The inhabitants appeared to think the spectacle of six girls dressed alike, with knapsacks in their hands (we always carried them thus in the towns), a curious and interesting one. We bought our viands, however, in spite of the eyes staring through the shop window at the transaction, and the noble president presented herself and us with a tin can, which the shopman filled with water for us.

Leaving Petworth, we went on only till out of the range of vision of its denizens, and then turning up a lane, we seated ourselves on the grass, and leaning against a gate, with our feet on our knapsacks, we lunched as comfortably as we could have done in our own dining-room. We were just congratulating ourselves on our privacy, too, when a gate at the end of the lane was opened, and a carriage and pair dashed past, its occupants gazing with astonishment at the merry party, and the various component parts of the luncheon that lay scattered around us.

It was always found that we walked better and with more enjoyment after lunch than before, and to-day was no exception. Passing along the pleasant lanes and across the open heaths, singing and telling tales to beguile the way, stiffness and blistered feet might have been things to us unknown, and we could hardly believe our day's walk was done, when we arrived at Pullborough.

As we left the village next morning, we heard a party of villagers speculating about us, and the president's gift evidently supplied them with a clue to our pursuits.

"They'll be painters, I reck'n," said one. "See the can that one is carrying? That's to hold the co'ours, that is."

Our road was said to be the Roman Stone Street. We could well believe it for, as our poet remarked, "it needs a great deal of the iron determination attributed to the Romans to tramp along this straight undeviating road." A bend or turn here or there would have been quite a relief; but no such weak-minded deviation from the severe straightness occurred.

At Billinghurst we were dismayed on visiting the only bread-shop to hear the owner say she had none left; but after a search in the back regions of her establishment she emerged with one very small loaf, all she had, and with that we had to be content. We lunched in a somewhat marshy spot, but the damp had happily no ill effects, being counteracted, perhaps, by our usual drink of tea each.

The day was very warm, and the president's can proved a great comfort, for we refilled it on every opportunity so as to be able to quench our thirst as we went along. This night, the last of our tour, we spent in a comfortable hotel at Horsham.

Saturday morning broke gloomy and threatening, but as it did not actually rain we determined to start as usual, and it was not till we were beyond the region of railways that the storm began in earnest. It was trying to have to put up with very limited view of the pretty country which is obtainable from beneath an umbrella; but as it was the only wet day we had, we tried to persuade ourselves that it was quite a pleasant variety.

Our pathfinder had spent the previous evening in measuring on her maps and counting up the distances of each day. She now told us that, on our arrival at the starting-place, we should have walked altogether 96 miles, making an average of 16 miles a day, though, as will have been seen, we had generally been either above or below the average.

The treasurer, too, had been busy with her account-book, and it may be of interest to my readers to know exactly what our tour cost. The total expenditure for the six of us during six days and five nights was £8 4s 6d, which gives £1 7s 5d as to the share of each, or 4s 6d each per day. This included everything, excepting only the president's noble gift of a tin can, value 3d. Our treasurer said that our plan of having "high tea" in the evening instead of dinner was an economical one. And, of course, taking our midday meal in the open air cost much less than having it at a hotel would have done, besides being much more agreeable. We should all have been very sorry to have missed the pleasure and fun of our daily picnics.

As we neared home the clouds broke, and the drops became few and far between.

"Look!" cried the artist, "there is quite a bright gleam of sunshine; we shall reach home under smiling skies after all."

"I believe we shall," said another of the party. "What a time of great enjoyment we have had! Do you know, I can't help thinking of this verse all the time -

Oh, God, oh Good beyond compare,

If thus Thine earthly works are fair,

How glorious will those mansions be

Where Thin elect shall dwell with Thee!"

For a moment or two we were all silent; then the president, looking up, cried - "See, there is our own home in sight. Now for a spurt, so as to come in gaily at last!" And so, with happy faces and thankful hearts, we marched up to the door, feeling, as we received the hearty welcome awaiting us, that we should be richer and better all our lives for the delightful hours spent in our walking tour.

Saturday, 28 May 2016

24 July 1880 - 'Tasty Dishes Quickly Prepared' by Phillis Browne

At least the recipe for "quick" beef tea at the end of this article does involve actually cooking it, unlike other recipes given elsewhere in the G.O.P.

One reason why the French are so superior to us as cooks is that they do not object to give both time and trouble to the preparation of their dishes. If only educated English girls would follow their example and give time, care, and forethought to cookery in their own homes, we should have many a father and brother strong and hearty who now looks white and delicate; we should have less waste in our kitchens, less bad temper in our families, and, I really believe, more thankfulness in our hearts.

Therefore when you see that I am going to speak about preparing dishes quickly, please do not imagine that I am recommending you to cook in a hurry. Things done hurriedly are generally done badly. It is my conviction that the time which a girl devotes to cookery is well and wisely spent.

Nevertheless there are occasions when it is necessary that our food should be quickly prepared, and it is for occasions of this kind that these recipes are given.

A friend of mine, a very clever housekeeper, once told me that for fifteen years she had never been without a neck of mutton in the house. Her husband was in business, and was in the habit of coming home hungry at unexpected time. She found that so many excellent and varied dishes could be made out of a neck of mutton, that she always had one hanging in her larder. She did not allow the butcher to joint it because it kept better whole, so that part of the business was done at home when required. The scrag end and the ends of the ribs were cooked separately, made into Irish stew or toad-in-the-hole, or hotch-potch or mutton broth. The best end alone was preserved for cutlets.

If mutton cutlets are bought ready trimmed at a shop the butcher will ask a very high price for them; indeed I have known people pay 1s 4d per pound for mutton cutlets. And they are very easily trimmed by those who can handle a small saw. The chine bone has to be removed, and also a piece about an inch and a half wide from the end of the rib bones. The flat bones which are on the meaty fillet of the neck are pared away, and the joint is separated into cutlets, one of which is cut with a bone and one without. The cutlets are then neatly trimmed, and a little of the fat is pared away from the end of the bone, leaving it bare a little way. When all this is done the cutlets are ready to be cooked.

Perhaps the best way of preparing cutlets is to broil them. For directions for cooking them thus I must ask you to refer to the paper on broiling which was given a little while ago. Well broiled cutlets are tender and full of flavour. If there is time to mash a few potatoes or to dress vegetables of any kind to serve with them, so much the better. The dressed vegetables may be piled in the centre of a hot dish, and the cutlets may be placed round them, one leaning on another. All vegetables after being cooked are improved by being shaken over the fire with a slice of butter before being sent to table.

If the fire is not in good condition for broiling, the cutlets may be cooked in a frying-pan as follows. Sprinkle a little pepper and salt on the cutlets. Rub a thick slice of stale crumb of bread through a sieve to make fine bread crumbs. Beat an egg in a plate, and brush the cutlets entirely over with it. Put the bread crumbs on a sheet of paper, lay the egged cutlets upon them on e at a time, and shake the corners of the paper, so as to toss the crumbs over the cutlets. Melt a slice of butter or dripping in a perfectly clean frying-pan, lay the cutlets in it, and cook them over a good fire. When the fat round them begins to get brown turn them over, and let them cook in the same way on the other side. Of course, we must remember not to stick a fork in the meat when we turn them.

Cutlets thus prepared may be made into different dishes by simply sending different sauces to table with them. Piquante sauce, for instance, is excellent. For this we make a quarter of a pint of melted butter in the usual way, and stir into it, at the last moment, four pickled gherkins that have been chopped quite small. A little of this sauce may be laid over each cutlet.

Melted butter is one of those things that every one knows how to make, and that is scarcely ever made well. Perhaps I may stop to describe how I think it should be made. It is a good plan to keep a very small stewpan specially for making sauces. An enamelled or tin stewpan will do excellently, although when it can be had, a porcelain stewpan is the best, because it can be cleaned so easily. I have a small porcelain stewpan that will hold three-quarters of a pint, and it has been in use a long time. Only I may say that I take charge of it myself, and am as careful about it as if it were a diamond ring. If it had been left to a careless servant it would have been broken long ago.

Melt an ounce and a half of butter in the stewpan, and draw the pan back and mix with it one ounce of flour. Beat flour and butter together until the mixture is quite smooth; then add, a little at a time, half-a-pint of cold water, and stir the sauce over the fire till it boils. Let it boil for three minutes, and it is ready. If liked, an ounce, instead of an ounce and a half of butter, may be used, or half good dripping and half butter may be taken.

Another very good sauce is made by chopping a moderate-sized onion till very small, and tossing it on the fire in a small stewpan with a small piece of butter for two or three minutes. When it is soft, and before it is at all coloured, pour over it a wineglassful of vinegar, and add an equal quantity of either stock or water. Simmer together for about five minutes, and add pepper and salt and a teaspoonful of mushroom ketchup, if liked. This sauce should be served in a tureen instead of being poured over the cutlets.

Perhaps it will be seen as if there were so many little details to attend to in the preparation of these dishes that they could scarcely be quickly prepared. But when the process is understood so that we can go on from one thing to another without waiting, and especially if we can arrange that bread crumbs can be passed through the sieve and gherkins or onions chopped beforehand, the work is soon done, and the result is decidedly satisfactory.

A broiled rump steak may also be quickly prepared, and if well cooked is sure to be enjoyed. It may be served without sauce, and is an excellent dish. Full directions for preparing it will be found in the paper on broiling.

Amongst homely dishes quickly prepared, what are called Scotch collops hold a foremost place. For this it is necessary only to have a little tender steak; buttock steak will answer the purpose excellently. Trim away all the fat and skin, and mince it finely. Dissolve a slice of butter or good beef dripping in a stewpan, put in the mince, and stir it well over the fire to prevent its gathering in lumps. In about eight minutes dredge a little flour over it, add gravy, or wanting this, water boiling hot, to moisten it. Season with pepper and salt, simmer a minute longer, and serve very hot. Mashed potatoes is a very good accompaniment to this dish also.

When good, fresh eggs are at hand they can quickly be transformed into an agreeable dish. There are said to be six hundred different way of serving an egg. I cannot answer for the truth of that, but I know that omelettes can be made of eggs, and that is praise enough. Omelettes are convenient preparations, too, because they can be varied to such an extent, and they are cheap, wholesome, and delicious. It is a very great pity that they are not more common amongst us, and yet somehow everyone seems afraid of making them. Let me advise you to try them. If you can make a plain omelette you can make every other kind, and then you need never be at a loss to furnish an elegant and delicious dish in a few minutes.

You will be very much more likely to succeed in making omelettes if you do not attempt very large ones. Three eggs will make a very good sized omelette. Also keep a little pan especially for the purpose; and never allow it to be washed; when it is done with let it be scraped and rubbed clean with a cloth, and wipe it out again with a cloth before using it. If it is washed the next omelette that is made for it will be a failure. The pan should be about six inches across, and can be bought for less than a shilling.

Break the eggs first into a cup, then into a basin, and season them with pepper and salt. Beat them lightly for three or four seconds and keep beating till the last moment. Whilst doing so, let the omelette pan be on the fire with about two ounces of fresh butter in it. AS soon as the butter froths turn the eggs into the pan, and stir them very quickly with a wooden spoon. When they begin to thicken raise the pan at one end, and keep the omelette at the lowest side till it is brown, moving the outside edges with the spoon. Turn it over quickly and put it on a hot dish. The outside should be a golden brown, and the inside should be quite soft, and the omelette should be a long oval shape. It can be made in two or three minutes. This seems simple enough, I dare say. So it is when once "the knack of it" is acquired. But there is quite an art in making an omelette, and this art can only be gained with practice.

Eggs, seasoned with pepper and salt, and cooked thus, form a plain omelette. If sweetened with sugar and flavoured with a few drops of vanilla, it would be a sweet omelette. If mixed with a teaspoonful of chopped parsley, and a piece of shallot the size of a pea, boiled, then chopped to dust, it would be savoury omelette. If gravy were poured round, we should have omelette with gravy. If the green points of boiled asparagus, or green peas were mixed with the eggs we should have omelette with asparagus, or omelette with green peas. If a dessert spoonful of grated cheese were added to the eggs, and a little more sprinkled on the top, we should have cheese omelette; or if a cooked sheep's kidney were cut into dice and mixed with the eggs, there would be omelette with kidneys; if a little jam (apricot jam is the kind usually preferred) were introduced into the centre, there would be apricot omelette; and if the flesh of tomatoes freed from skin and seeds were mixed with the eggs, there would be omelette with tomatoes.

When it is wished that food should be quickly prepared, tinned provisions are particularly valuable. I know quite well that a strong prejudice exists against these meats in many quarters, and I think the feeling is a little unreasonable. Of course I do not maintain that tinned meat, even when served in perfection, is as good as a freshly broiled rump steak; but I do say that it is an advantage, especially for those who are likely to have unexpected calls upon their resources, to have in the house one or two varieties of preserved food. This food does not spoil with keeping; and it will always be at hand when wanted. The only precaution that needs to be observed in buying it is to secure a good brand.

Tinned soups are especially excellent. The objection is frequently urged against them that they taste of the tin. This can be removed, however, by boiling fresh vegetables such as were likely to be used originally in flavouring the soup with a small quantity of fresh stock, and adding this with half a tea-spoonful of extract of meat, and a little brown thickening to the contents of the tins, and then making all hot together. By this means not only will the "tinny" taste be removed, and the flavour of the soup will be revived, but its quantity will be increased, and it will be made to "go further."

Tinned vegetables on the other hand are improved by having a little sugar put with them when they are made hot, while, in addition, peas can have a sprig of mint, or mixed vegetables a bunch of parsley, put into the saucepan with them. Tinned apricots and peaches can have a drop of almond flavouring added to the syrup. By the help of little manoeuvres of this kind food can be made to taste very much like fresh good tinned food.

Before I close I must say one word about making beef tea quickly. I am a great believer in good beef tea. Whenever any of my friends get below par, and take cold quickly and are generally out of sorts, I always feel a desire to make them take twice or three times a day, and in addition to their ordinary food, a cupful of good, strong beef tea. I mean good home-made beef tea, made from the roll of the bladebone of beef, and tasting as if it would give energy and strength.

It takes time, however, to make beef tea like this, and sometimes the tea is wanted quickly. When this is the case, take half a pound of lean juicy meat - the roll of the bladebone is the best part for this purpose - and trim away both fat and skin. Cut the meat into very small pieces, sprinkle a little salt over it, and pour upon it a small tumblerful of cold water. Bring it to the boil, stirring it all the time; ;et it simmer for five minutes, and it is ready to serve.

One reason why the French are so superior to us as cooks is that they do not object to give both time and trouble to the preparation of their dishes. If only educated English girls would follow their example and give time, care, and forethought to cookery in their own homes, we should have many a father and brother strong and hearty who now looks white and delicate; we should have less waste in our kitchens, less bad temper in our families, and, I really believe, more thankfulness in our hearts.

Therefore when you see that I am going to speak about preparing dishes quickly, please do not imagine that I am recommending you to cook in a hurry. Things done hurriedly are generally done badly. It is my conviction that the time which a girl devotes to cookery is well and wisely spent.

Nevertheless there are occasions when it is necessary that our food should be quickly prepared, and it is for occasions of this kind that these recipes are given.

A friend of mine, a very clever housekeeper, once told me that for fifteen years she had never been without a neck of mutton in the house. Her husband was in business, and was in the habit of coming home hungry at unexpected time. She found that so many excellent and varied dishes could be made out of a neck of mutton, that she always had one hanging in her larder. She did not allow the butcher to joint it because it kept better whole, so that part of the business was done at home when required. The scrag end and the ends of the ribs were cooked separately, made into Irish stew or toad-in-the-hole, or hotch-potch or mutton broth. The best end alone was preserved for cutlets.

If mutton cutlets are bought ready trimmed at a shop the butcher will ask a very high price for them; indeed I have known people pay 1s 4d per pound for mutton cutlets. And they are very easily trimmed by those who can handle a small saw. The chine bone has to be removed, and also a piece about an inch and a half wide from the end of the rib bones. The flat bones which are on the meaty fillet of the neck are pared away, and the joint is separated into cutlets, one of which is cut with a bone and one without. The cutlets are then neatly trimmed, and a little of the fat is pared away from the end of the bone, leaving it bare a little way. When all this is done the cutlets are ready to be cooked.

Perhaps the best way of preparing cutlets is to broil them. For directions for cooking them thus I must ask you to refer to the paper on broiling which was given a little while ago. Well broiled cutlets are tender and full of flavour. If there is time to mash a few potatoes or to dress vegetables of any kind to serve with them, so much the better. The dressed vegetables may be piled in the centre of a hot dish, and the cutlets may be placed round them, one leaning on another. All vegetables after being cooked are improved by being shaken over the fire with a slice of butter before being sent to table.

If the fire is not in good condition for broiling, the cutlets may be cooked in a frying-pan as follows. Sprinkle a little pepper and salt on the cutlets. Rub a thick slice of stale crumb of bread through a sieve to make fine bread crumbs. Beat an egg in a plate, and brush the cutlets entirely over with it. Put the bread crumbs on a sheet of paper, lay the egged cutlets upon them on e at a time, and shake the corners of the paper, so as to toss the crumbs over the cutlets. Melt a slice of butter or dripping in a perfectly clean frying-pan, lay the cutlets in it, and cook them over a good fire. When the fat round them begins to get brown turn them over, and let them cook in the same way on the other side. Of course, we must remember not to stick a fork in the meat when we turn them.

Cutlets thus prepared may be made into different dishes by simply sending different sauces to table with them. Piquante sauce, for instance, is excellent. For this we make a quarter of a pint of melted butter in the usual way, and stir into it, at the last moment, four pickled gherkins that have been chopped quite small. A little of this sauce may be laid over each cutlet.

Melted butter is one of those things that every one knows how to make, and that is scarcely ever made well. Perhaps I may stop to describe how I think it should be made. It is a good plan to keep a very small stewpan specially for making sauces. An enamelled or tin stewpan will do excellently, although when it can be had, a porcelain stewpan is the best, because it can be cleaned so easily. I have a small porcelain stewpan that will hold three-quarters of a pint, and it has been in use a long time. Only I may say that I take charge of it myself, and am as careful about it as if it were a diamond ring. If it had been left to a careless servant it would have been broken long ago.

Melt an ounce and a half of butter in the stewpan, and draw the pan back and mix with it one ounce of flour. Beat flour and butter together until the mixture is quite smooth; then add, a little at a time, half-a-pint of cold water, and stir the sauce over the fire till it boils. Let it boil for three minutes, and it is ready. If liked, an ounce, instead of an ounce and a half of butter, may be used, or half good dripping and half butter may be taken.

Another very good sauce is made by chopping a moderate-sized onion till very small, and tossing it on the fire in a small stewpan with a small piece of butter for two or three minutes. When it is soft, and before it is at all coloured, pour over it a wineglassful of vinegar, and add an equal quantity of either stock or water. Simmer together for about five minutes, and add pepper and salt and a teaspoonful of mushroom ketchup, if liked. This sauce should be served in a tureen instead of being poured over the cutlets.

Perhaps it will be seen as if there were so many little details to attend to in the preparation of these dishes that they could scarcely be quickly prepared. But when the process is understood so that we can go on from one thing to another without waiting, and especially if we can arrange that bread crumbs can be passed through the sieve and gherkins or onions chopped beforehand, the work is soon done, and the result is decidedly satisfactory.

A broiled rump steak may also be quickly prepared, and if well cooked is sure to be enjoyed. It may be served without sauce, and is an excellent dish. Full directions for preparing it will be found in the paper on broiling.

Amongst homely dishes quickly prepared, what are called Scotch collops hold a foremost place. For this it is necessary only to have a little tender steak; buttock steak will answer the purpose excellently. Trim away all the fat and skin, and mince it finely. Dissolve a slice of butter or good beef dripping in a stewpan, put in the mince, and stir it well over the fire to prevent its gathering in lumps. In about eight minutes dredge a little flour over it, add gravy, or wanting this, water boiling hot, to moisten it. Season with pepper and salt, simmer a minute longer, and serve very hot. Mashed potatoes is a very good accompaniment to this dish also.

When good, fresh eggs are at hand they can quickly be transformed into an agreeable dish. There are said to be six hundred different way of serving an egg. I cannot answer for the truth of that, but I know that omelettes can be made of eggs, and that is praise enough. Omelettes are convenient preparations, too, because they can be varied to such an extent, and they are cheap, wholesome, and delicious. It is a very great pity that they are not more common amongst us, and yet somehow everyone seems afraid of making them. Let me advise you to try them. If you can make a plain omelette you can make every other kind, and then you need never be at a loss to furnish an elegant and delicious dish in a few minutes.

You will be very much more likely to succeed in making omelettes if you do not attempt very large ones. Three eggs will make a very good sized omelette. Also keep a little pan especially for the purpose; and never allow it to be washed; when it is done with let it be scraped and rubbed clean with a cloth, and wipe it out again with a cloth before using it. If it is washed the next omelette that is made for it will be a failure. The pan should be about six inches across, and can be bought for less than a shilling.

Break the eggs first into a cup, then into a basin, and season them with pepper and salt. Beat them lightly for three or four seconds and keep beating till the last moment. Whilst doing so, let the omelette pan be on the fire with about two ounces of fresh butter in it. AS soon as the butter froths turn the eggs into the pan, and stir them very quickly with a wooden spoon. When they begin to thicken raise the pan at one end, and keep the omelette at the lowest side till it is brown, moving the outside edges with the spoon. Turn it over quickly and put it on a hot dish. The outside should be a golden brown, and the inside should be quite soft, and the omelette should be a long oval shape. It can be made in two or three minutes. This seems simple enough, I dare say. So it is when once "the knack of it" is acquired. But there is quite an art in making an omelette, and this art can only be gained with practice.

Eggs, seasoned with pepper and salt, and cooked thus, form a plain omelette. If sweetened with sugar and flavoured with a few drops of vanilla, it would be a sweet omelette. If mixed with a teaspoonful of chopped parsley, and a piece of shallot the size of a pea, boiled, then chopped to dust, it would be savoury omelette. If gravy were poured round, we should have omelette with gravy. If the green points of boiled asparagus, or green peas were mixed with the eggs we should have omelette with asparagus, or omelette with green peas. If a dessert spoonful of grated cheese were added to the eggs, and a little more sprinkled on the top, we should have cheese omelette; or if a cooked sheep's kidney were cut into dice and mixed with the eggs, there would be omelette with kidneys; if a little jam (apricot jam is the kind usually preferred) were introduced into the centre, there would be apricot omelette; and if the flesh of tomatoes freed from skin and seeds were mixed with the eggs, there would be omelette with tomatoes.

When it is wished that food should be quickly prepared, tinned provisions are particularly valuable. I know quite well that a strong prejudice exists against these meats in many quarters, and I think the feeling is a little unreasonable. Of course I do not maintain that tinned meat, even when served in perfection, is as good as a freshly broiled rump steak; but I do say that it is an advantage, especially for those who are likely to have unexpected calls upon their resources, to have in the house one or two varieties of preserved food. This food does not spoil with keeping; and it will always be at hand when wanted. The only precaution that needs to be observed in buying it is to secure a good brand.

Tinned soups are especially excellent. The objection is frequently urged against them that they taste of the tin. This can be removed, however, by boiling fresh vegetables such as were likely to be used originally in flavouring the soup with a small quantity of fresh stock, and adding this with half a tea-spoonful of extract of meat, and a little brown thickening to the contents of the tins, and then making all hot together. By this means not only will the "tinny" taste be removed, and the flavour of the soup will be revived, but its quantity will be increased, and it will be made to "go further."

Tinned vegetables on the other hand are improved by having a little sugar put with them when they are made hot, while, in addition, peas can have a sprig of mint, or mixed vegetables a bunch of parsley, put into the saucepan with them. Tinned apricots and peaches can have a drop of almond flavouring added to the syrup. By the help of little manoeuvres of this kind food can be made to taste very much like fresh good tinned food.

Before I close I must say one word about making beef tea quickly. I am a great believer in good beef tea. Whenever any of my friends get below par, and take cold quickly and are generally out of sorts, I always feel a desire to make them take twice or three times a day, and in addition to their ordinary food, a cupful of good, strong beef tea. I mean good home-made beef tea, made from the roll of the bladebone of beef, and tasting as if it would give energy and strength.

It takes time, however, to make beef tea like this, and sometimes the tea is wanted quickly. When this is the case, take half a pound of lean juicy meat - the roll of the bladebone is the best part for this purpose - and trim away both fat and skin. Cut the meat into very small pieces, sprinkle a little salt over it, and pour upon it a small tumblerful of cold water. Bring it to the boil, stirring it all the time; ;et it simmer for five minutes, and it is ready to serve.

Wednesday, 25 May 2016

17 July 1880 - Answers to Correspondents - Miscellaneous

MARION - We thank you for your long kind letter so full of appreciation of our paper. We feel much sympathy with you in the very difficult position in which you are placed, and feel anxious in giving you advice, lest you should lose your situation from acting upon it. But we can only tell you what we should do under similar circumstances. A line must be drawn somewhere in your endurance of disrespect and the defiance of your rightful authority; or you cannot do your duty by your employers nor by your young charges. Rude words may be punished in many ways without your making a formal complaint to the parents; but to rude actions - such as striking, scratching, etc. - you would do wrong to submit. Take an opportunity when both father and mother are together, and in a quiet, yet firm, manner tell them you wish to lay certain matters before them, and to ask their advice and their assistance; that you are bound in honour to give notice, as a duty owed to them as well as to yourself, if unable to sustain your authority and to make yourself respected, for that you must train the children in morals, as well as merely teach them lessons. Say you cannot tolerate the children laying hands on you and that you must ask them to interfere on any such occasion. Perhaps you had better write a letter to this effect, stating all in as few words as possible, and very kindly and respectfully. Should you do so, let us hear the results.

HENRIETTE - 1. It is not at all necessary to introduce people who meet you to the friend walking with you. 2. The younger, or unmarried person, or inferior in rank or position, should be introduced to the older or more important person. 3. We cannot tell you what openings may exist at Dundee for employments of any kind.

ZETA - 1. The best remedy for low spirits is to attend to your digestion, and take care that the liver be not at fault; to be out a good deal, and to work in a garden, if you have a nice sunny one; to associate with cheerful companions of your own age; to occupy yourself continually in various useful ways, by which you can be of use to others, and endeavour to cheer them and help them, if old or out of health, over the monotony of enforced idleness. Try, in fact, to make it one of your objects in life to make someone else more happy. Never be idle for a moment, and take regular daily exercise without over fatigue. 2. The best modern history of England is Green's. 3. Painting, in all its branches, appears to be the art most in fashion at present. 4. A coil of plaits at the back of the head - now the style most in vogue - would be suitable for wear in riding, and out of the way of a hat.

IDA - You have fed the jackdaws quite properly. They will soon eat anything that you can, and many things that you can't. We think your writing is poor, and are glad you like THE GIRL'S OWN PAPER.

HENRIETTE - 1. It is not at all necessary to introduce people who meet you to the friend walking with you. 2. The younger, or unmarried person, or inferior in rank or position, should be introduced to the older or more important person. 3. We cannot tell you what openings may exist at Dundee for employments of any kind.

ZETA - 1. The best remedy for low spirits is to attend to your digestion, and take care that the liver be not at fault; to be out a good deal, and to work in a garden, if you have a nice sunny one; to associate with cheerful companions of your own age; to occupy yourself continually in various useful ways, by which you can be of use to others, and endeavour to cheer them and help them, if old or out of health, over the monotony of enforced idleness. Try, in fact, to make it one of your objects in life to make someone else more happy. Never be idle for a moment, and take regular daily exercise without over fatigue. 2. The best modern history of England is Green's. 3. Painting, in all its branches, appears to be the art most in fashion at present. 4. A coil of plaits at the back of the head - now the style most in vogue - would be suitable for wear in riding, and out of the way of a hat.

IDA - You have fed the jackdaws quite properly. They will soon eat anything that you can, and many things that you can't. We think your writing is poor, and are glad you like THE GIRL'S OWN PAPER.

Tuesday, 24 May 2016

17 July 1880 - 'Nursing as a Profession' by S.F.A. Caulfield

I am given to understand that many of the readers of this paper are anxious to obtain all the information that can be procured on the subject of nursing, with a view to its selection as their vocation in life. The task of writing an article on this question is one of some little difficulty. Although regarding it as a grand profession, and one supplied with a staff most inadequate in numbers for a population such as ours, I decline the responsibility of recommending it, or of dissuading those disposed to join its ranks. According to the rough calculation made, and that probably under the mark, "to nurse the sick of all England properly, twenty-five thousand trained nurses, officered by one thousand fully-trained lady-superintendents, are required." In such hands with the work to be done could be fairly proportioned.

Before supplying any information as to the schools and hospitals in which the requisite training can be obtained, the individual qualifications for a nurse should be carefully considered. These may be classed as mental, moral, and physical; each and all being indispensible in a "probationer."

Under the mental and moral she must possess good temper, self-control, patience, punctuality, cheerfulness, and a willing obedience to those in authority over her. Under the physical, good health, good sight, a delicate touch, quickness of hearing, dexterous fingers, cleanliness, and suitability of age. A chronic cough, a heavy tread, a tendency to faint, or to attacks of hysterics, any description of deformity, or repulsiveness in appearance and expression, would disqualify a candidate for permanent employment as a nurse.

Furthermore, it is only fair to those having so arduous a calling in contemplation, to prepare them for loss of rest, painful scenes, and the necessity for the performance of every office that one human being could perform for another, both to relieve suffering, and to render the surroundings of a sick bed as comfortable and cheerful as possible.

No "fine lady" who calls any charitable service "menial work" should adopt such a vocation. And besides the trial of performing personally repugnant and painful duties, the ill-temper, ingratitude, and fretfulness of her charge must all be anticipated, and accepted patiently, as a part of the sacrifice that a nurse has to make.

Nursing should not be lightly undertaken, nor merely as a means of obtaining a livelihood. A competence, a home, an interest in life, and in some cases a small pension, are to be found by the professional nurse, but certainly not a fortune.

Judging from those whom I have seen or known, they seem to be happy and contented, and even cheerful; yet with a certain amount of gravity, which an intimacy with so much suffering must inevitably produce. But the cheerfulness can be quite as naturally accounted for in the fact that, they are able to assuage that pain, to aid so much in the cures effected, and to comfort the sad and sorrowful. You may now weigh the blessedness of the work against all its trials and self-denials, and then deliberately make your decision.

The profession is divided into three departments - viz., District Nursing, Hospital Nursing, and Private Nursing. Thus the intending nurse has some choice permitted her in the description of work to be done, and the external circumstances with which she would prefer to be surrounded. Beginning with the first-named departments - giving, as I consider, the severest description of work - I cannot do better than quote from Florence Nightingale, when she describes the extra labour incumbent on the "district nurse," over and above the personal attendance / sick. For instance, she goes into a dirty, squalid-looking room, and before she can hope for any change for the better in her patient, she must "recreate the home," and "show it clean for once; sweep and dust away; empty and wash out the dirt; air and disinfect; rub the windows, sweep the fireplace; carry out, shake, and replace the scraps of carpet; lay them down again, fetch fresh water, fill the kettle, wash the patient and the children, and make the bed." Besides this she must "bring such sanitary defects as produce sickness and death to the notice of the public officer whom it concerns."

Having shown the dark side of the picture, I proceed to tell that the district nurse is well cared for when she returns to the home provided for her, and the pleasant companionship of those who have selected the same honourable profession. I need not enter into particulars, as the intending nurse should visit the several institutions where training is to be obtained. Let her see the home for herself, learn its rules, and take a view of the prospect which would open before her, as a probationer in one of the twenty-two institutions that train for themselves, or supply other hospitals.

The "Institution for Nursing Sisters" in Devonshire-square, is the oldest of the kind, and was established in 1840. It provides no less than 20 districts each with a nurse free of charge, but untrained; and trained ones for those who can pay for their services.

With the "Metropolitan and National Association' for providing trained nurses for the poor (free of charge) I have had some acquaintance, for through the kindness of Miss Florence Lees, late Superintendent-General of the institution, I have inspected every part of the central home in Bloomsbury-square. The four branch homes connected with it are all governed by the same regulations. In these houses candidates reside for a month on trial, and if suitable are passed on to the Hospital Training School, as "nurse probationers," to receive a year's training in hospital nursing. They are then returned to the Central Home to be trained in "district nursing," receiving technical class instruction during a period of three months, when, if found satisfactory, they are entered on a register, and placed on the staff of the association. A member so enrolled is expected to continue in the service of the association for three years, three months' notice being given on either side, should a termination of the engagement be desired. Nurse candidates have to pay £5 on admission to the home, to cover the expense of her board, lodging, and washing during the month of trial.

For the year's training in St. Thomas's Hospital Training School the probationers pay £15 on admission, and £15 after six months of residence and training. For this she will have full board, 1s 6d a week for washing, a uniform dress, a separate furnished bed-room, and the use of a common sitting-room. The instruction is paid for out of the "Nightingale Fund," but in case of dismissal, or of voluntary withdrawal the cost will be charged.

When the probationer returns to the home, after the year's training, she will have to pay in advance £14 for three months' training in "district nursing," class instruction, books, full board, and extras; 2s 6d allowance weekly for washing; a separate room (or compartment), and the general sitting-room. Once fully trained, and on the staff of the association, the nurse receives a salary, payable quarterly, of £35 for the first year, £38 for the second, and so on, increasing by £3 yearly until the sixth year, when it will amount to £50 per annum, in addition to their uniform dress, full board, separate bed-room, washing, etc.

From giving a sketch of the terms on which the candidate enters the "Metropolitan Nursing Association," I will give a general idea of those of other institutions. The age at which a candidate is taken varies between twenty-five and forty. At St. Thomas's Hospital she enters as a "Nightingale probationer," at a rising salary, beginning at £10, with partial uniform; and her services are at the disposal of the committee for a period of four years. Here ladies may be trained on a payment of a £30 premium, and after one year will receive a salary rising from £25 to £50, but they are expected to give their service for four years.

At the Royal Free Hospital (Gray's Inn-road) the nursing is done by the "Training School of Protestant Nurses," of Cambridge-place, Paddington, and probationers begin with a salary equivalent to fourteen guineas, rising to £25. Here they give a three months' training at the rate of £1 15s per week, or £30 for one year. In this latter case they are required to give their services for a period of two years extra.

At the Middlesex Hospital lady pupils are receives for not less than six months at one guinea a week. Probationers begin with a salary of £12, rising to £18 after the first year, and then by £2 yearly up to £26.

At the London Hospital "nurse probationers" receive £12 on admission, rising to £21; but they are not promoted to be "sisters." These latter are educated women entering as "sister probationers," whose salary begins at £25 six months after their admission. Both these and the nurses are required to remain three years in the hospital.

At King's College and Charing Cross Hospitals, probationers receive £15 per annum and their uniform. They are bound for three years' service, an engagement renewable for another three years, with a rising salary. Both hospitals are nursed by the community of "St. John's House," Norfolk-street, Strand. Pupil nurses for district work or other institutions are trained for six months at the rate of £24 per annum. Ladies also are trained for not less than three months at a rate of £50 per annum.

At Westminster Hospital probationers begin with £16 per annum. If willing to pay £52 for their training, they are not required to remain there beyond it.

At University College Hospital nurses receive £16 per annum, and everything found for them.

St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, trains gentlewomen and nurses desirous of qualifying for public appointments, or private nursing for one year. If required by the matrons so to do, they remain for fifteen months. They serve then as assistant-nurses, and are paid at the rate of £10 and uniform. Those who pass this year of probation satisfactorily are entered in a register, and recommended for employment.

The Deaconess Institution and Training Hospital will train women of known religious character gratuitously, if they propose to become deaconesses; and will supply them as nurses to public institutions at £12 per annum. (The Green, Tottenham, N.) These have a branch institution at Mildmay Park, and a hospital at Poplar.

The Institution of Nursing Sisters, in Devonshire-square, supply's Guy's Hospital, where the annual salary of sisters amounts to £50 and dresses, and which has a Superannuation Fund for them.

Nurses are also trained at St. Bartholomew's and other institutions in town, including the Children's Hospital (Great Ormond-street), where lady pupils are received of from 21 to 35 years of age, at one guinea a week; and nurses of from 17 to 35 years at 7s 6d a week, for not less than six months. At the London North-Eastern Hospital ladies are received for training at a guinea a week.

In Edinburgh and Dublin, at Liverpool, Manchester, Cambridge, Leeds, Winchester, Leicester, Rhyl, Nottingham, and elsewhere, training is to be obtained.

There are other descriptions of work connected with the profession of nursing, such as, for instance, tending the insane, into which it is not necessary that I should enter in this article. Were I to give my private opinion as to the nature of the work to be performed, in the three departments to which I have referred I should say that "district nursing" was the severest of all; hospital nursing ranking next, in the trying nature of its experiences; and private nursing the least troublesome, allowing, of course, for some exceptional cases.

I have only named a few of the training schools for intending probationers, amongst the twenty-two or more valuable institutions which exist in London or its suburbs. Of the "Bible and Domestic Female Mission" at 13, Hunter-street, of which Mrs. Ranyard was founder, I should have made a particular mention, but that our magazine is especially designed for young people, whereas the nurses connected with this missionary society are required to be nearly of middle age. Still, the young nurse may have this institution in view, as providing a sphere of usefulness for her of a two-fold character in her after life.

Of such a sacred vocation as that of nursing it may indeed be truly said that

"If it is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives, and him that takes."

Before supplying any information as to the schools and hospitals in which the requisite training can be obtained, the individual qualifications for a nurse should be carefully considered. These may be classed as mental, moral, and physical; each and all being indispensible in a "probationer."

Under the mental and moral she must possess good temper, self-control, patience, punctuality, cheerfulness, and a willing obedience to those in authority over her. Under the physical, good health, good sight, a delicate touch, quickness of hearing, dexterous fingers, cleanliness, and suitability of age. A chronic cough, a heavy tread, a tendency to faint, or to attacks of hysterics, any description of deformity, or repulsiveness in appearance and expression, would disqualify a candidate for permanent employment as a nurse.

Furthermore, it is only fair to those having so arduous a calling in contemplation, to prepare them for loss of rest, painful scenes, and the necessity for the performance of every office that one human being could perform for another, both to relieve suffering, and to render the surroundings of a sick bed as comfortable and cheerful as possible.

No "fine lady" who calls any charitable service "menial work" should adopt such a vocation. And besides the trial of performing personally repugnant and painful duties, the ill-temper, ingratitude, and fretfulness of her charge must all be anticipated, and accepted patiently, as a part of the sacrifice that a nurse has to make.

Nursing should not be lightly undertaken, nor merely as a means of obtaining a livelihood. A competence, a home, an interest in life, and in some cases a small pension, are to be found by the professional nurse, but certainly not a fortune.

Judging from those whom I have seen or known, they seem to be happy and contented, and even cheerful; yet with a certain amount of gravity, which an intimacy with so much suffering must inevitably produce. But the cheerfulness can be quite as naturally accounted for in the fact that, they are able to assuage that pain, to aid so much in the cures effected, and to comfort the sad and sorrowful. You may now weigh the blessedness of the work against all its trials and self-denials, and then deliberately make your decision.

The profession is divided into three departments - viz., District Nursing, Hospital Nursing, and Private Nursing. Thus the intending nurse has some choice permitted her in the description of work to be done, and the external circumstances with which she would prefer to be surrounded. Beginning with the first-named departments - giving, as I consider, the severest description of work - I cannot do better than quote from Florence Nightingale, when she describes the extra labour incumbent on the "district nurse," over and above the personal attendance / sick. For instance, she goes into a dirty, squalid-looking room, and before she can hope for any change for the better in her patient, she must "recreate the home," and "show it clean for once; sweep and dust away; empty and wash out the dirt; air and disinfect; rub the windows, sweep the fireplace; carry out, shake, and replace the scraps of carpet; lay them down again, fetch fresh water, fill the kettle, wash the patient and the children, and make the bed." Besides this she must "bring such sanitary defects as produce sickness and death to the notice of the public officer whom it concerns."

Having shown the dark side of the picture, I proceed to tell that the district nurse is well cared for when she returns to the home provided for her, and the pleasant companionship of those who have selected the same honourable profession. I need not enter into particulars, as the intending nurse should visit the several institutions where training is to be obtained. Let her see the home for herself, learn its rules, and take a view of the prospect which would open before her, as a probationer in one of the twenty-two institutions that train for themselves, or supply other hospitals.

The "Institution for Nursing Sisters" in Devonshire-square, is the oldest of the kind, and was established in 1840. It provides no less than 20 districts each with a nurse free of charge, but untrained; and trained ones for those who can pay for their services.

With the "Metropolitan and National Association' for providing trained nurses for the poor (free of charge) I have had some acquaintance, for through the kindness of Miss Florence Lees, late Superintendent-General of the institution, I have inspected every part of the central home in Bloomsbury-square. The four branch homes connected with it are all governed by the same regulations. In these houses candidates reside for a month on trial, and if suitable are passed on to the Hospital Training School, as "nurse probationers," to receive a year's training in hospital nursing. They are then returned to the Central Home to be trained in "district nursing," receiving technical class instruction during a period of three months, when, if found satisfactory, they are entered on a register, and placed on the staff of the association. A member so enrolled is expected to continue in the service of the association for three years, three months' notice being given on either side, should a termination of the engagement be desired. Nurse candidates have to pay £5 on admission to the home, to cover the expense of her board, lodging, and washing during the month of trial.

For the year's training in St. Thomas's Hospital Training School the probationers pay £15 on admission, and £15 after six months of residence and training. For this she will have full board, 1s 6d a week for washing, a uniform dress, a separate furnished bed-room, and the use of a common sitting-room. The instruction is paid for out of the "Nightingale Fund," but in case of dismissal, or of voluntary withdrawal the cost will be charged.

When the probationer returns to the home, after the year's training, she will have to pay in advance £14 for three months' training in "district nursing," class instruction, books, full board, and extras; 2s 6d allowance weekly for washing; a separate room (or compartment), and the general sitting-room. Once fully trained, and on the staff of the association, the nurse receives a salary, payable quarterly, of £35 for the first year, £38 for the second, and so on, increasing by £3 yearly until the sixth year, when it will amount to £50 per annum, in addition to their uniform dress, full board, separate bed-room, washing, etc.

From giving a sketch of the terms on which the candidate enters the "Metropolitan Nursing Association," I will give a general idea of those of other institutions. The age at which a candidate is taken varies between twenty-five and forty. At St. Thomas's Hospital she enters as a "Nightingale probationer," at a rising salary, beginning at £10, with partial uniform; and her services are at the disposal of the committee for a period of four years. Here ladies may be trained on a payment of a £30 premium, and after one year will receive a salary rising from £25 to £50, but they are expected to give their service for four years.

At the Royal Free Hospital (Gray's Inn-road) the nursing is done by the "Training School of Protestant Nurses," of Cambridge-place, Paddington, and probationers begin with a salary equivalent to fourteen guineas, rising to £25. Here they give a three months' training at the rate of £1 15s per week, or £30 for one year. In this latter case they are required to give their services for a period of two years extra.

At the Middlesex Hospital lady pupils are receives for not less than six months at one guinea a week. Probationers begin with a salary of £12, rising to £18 after the first year, and then by £2 yearly up to £26.

At the London Hospital "nurse probationers" receive £12 on admission, rising to £21; but they are not promoted to be "sisters." These latter are educated women entering as "sister probationers," whose salary begins at £25 six months after their admission. Both these and the nurses are required to remain three years in the hospital.

At King's College and Charing Cross Hospitals, probationers receive £15 per annum and their uniform. They are bound for three years' service, an engagement renewable for another three years, with a rising salary. Both hospitals are nursed by the community of "St. John's House," Norfolk-street, Strand. Pupil nurses for district work or other institutions are trained for six months at the rate of £24 per annum. Ladies also are trained for not less than three months at a rate of £50 per annum.

At Westminster Hospital probationers begin with £16 per annum. If willing to pay £52 for their training, they are not required to remain there beyond it.

At University College Hospital nurses receive £16 per annum, and everything found for them.

St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, trains gentlewomen and nurses desirous of qualifying for public appointments, or private nursing for one year. If required by the matrons so to do, they remain for fifteen months. They serve then as assistant-nurses, and are paid at the rate of £10 and uniform. Those who pass this year of probation satisfactorily are entered in a register, and recommended for employment.

The Deaconess Institution and Training Hospital will train women of known religious character gratuitously, if they propose to become deaconesses; and will supply them as nurses to public institutions at £12 per annum. (The Green, Tottenham, N.) These have a branch institution at Mildmay Park, and a hospital at Poplar.

The Institution of Nursing Sisters, in Devonshire-square, supply's Guy's Hospital, where the annual salary of sisters amounts to £50 and dresses, and which has a Superannuation Fund for them.

Nurses are also trained at St. Bartholomew's and other institutions in town, including the Children's Hospital (Great Ormond-street), where lady pupils are received of from 21 to 35 years of age, at one guinea a week; and nurses of from 17 to 35 years at 7s 6d a week, for not less than six months. At the London North-Eastern Hospital ladies are received for training at a guinea a week.

In Edinburgh and Dublin, at Liverpool, Manchester, Cambridge, Leeds, Winchester, Leicester, Rhyl, Nottingham, and elsewhere, training is to be obtained.

There are other descriptions of work connected with the profession of nursing, such as, for instance, tending the insane, into which it is not necessary that I should enter in this article. Were I to give my private opinion as to the nature of the work to be performed, in the three departments to which I have referred I should say that "district nursing" was the severest of all; hospital nursing ranking next, in the trying nature of its experiences; and private nursing the least troublesome, allowing, of course, for some exceptional cases.

I have only named a few of the training schools for intending probationers, amongst the twenty-two or more valuable institutions which exist in London or its suburbs. Of the "Bible and Domestic Female Mission" at 13, Hunter-street, of which Mrs. Ranyard was founder, I should have made a particular mention, but that our magazine is especially designed for young people, whereas the nurses connected with this missionary society are required to be nearly of middle age. Still, the young nurse may have this institution in view, as providing a sphere of usefulness for her of a two-fold character in her after life.

Of such a sacred vocation as that of nursing it may indeed be truly said that

"If it is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives, and him that takes."

Labels:

employment,

finance,

money,

nursing,

s.f.a. caulfield,

work

Saturday, 21 May 2016

17 July 1880 - 'What Our Girls May Do' by Alice King

You may do anything that is good and proper and useful - except anything that men do, that would be wrong.

We do not want to say what our girls may not do, because "may not" has a sound of the schoolroom about it which would take away from the pleasant freedom of the little chat we mean to have with our girls today. That our talk together may be more cheery and hearty we will ask our girls to fancy themselves sitting with us around the Christmas fire, with the frosty air outside filled with the glitter of stars and the melody of bells; or wandering through the summer woods, with their hands filled with honeysuckle and yellow pimpernel and musk-scented stork's-bill, with bird and brook making fair harmony hard by.

In the first place, our girls may try to do anything which is useful. They love to play at being useful from the time when they can first toddle, and they may begin to do it in earnest as soon as ever they are able. But how can we be useful, they will ask? They can begin very early to do a deal of good in their families by influencing their younger brothers and sisters, by keeping the rough word off the little boy's lips, by showing the tiny maiden that to be a Christian girl means to be as bright as the flowers, as full of their sweetness that spreads perfume round; is to be as pure as the dewdrop, as blithe as the skylark's song. The little ones are far more free n talk and manner with you than they are with elder people, and so you have opportunities with them which do not belong even to their mothers.

Our girls may also do much in the way of influencing their schoolboy brothers, and instilling into them reverence for womanhood. Girls are too much inclined to look upon it as a merit to give themselves up patiently to be teased by their brothers. Far from this, they should show them that even the sweetest tempered girl has a touch of queenliness about her, which demands a certain degree of careful, tender respect from men, which forbids rude acts and words in her presence. Thus will our lads learn early from their sisters the meaning of chivalry, and every woman whom they shall meet in their life's journey will bless those sisters for what they did long ago.

There is good work at home for our girls in giving a high, right tone of thought and feeling to young female servants. Girls, perhaps, are not aware how much their dress and manners form the dress and manners of the servants' hall and kitchen; and there is no truer saying than that servants grow like their mistresses. They should, therefore, endeavour to show any girls of a lower social rank than their own what is the meaning of modest grace, of Christian womanliness. They should seek to make them feel that they are their friends, and to win their confidence, so that they will tell them all their little troubles and difficulties, and let themselves be helped by the young ladies' superior intelligence and education. They should provide, as far as they can, rational amusements for them; they should send or take them to places of interest, Bible classes, and sewing parties.